- 当日発送

- 送料無料

本物品質の SONY / ソニー HD DIGITAL VIDEOCASSETTE RECORDER HDW-S2000 HDCAMレコーダー オーディオ機器 再生機器 ベータカム

- 販売価格 :

-

¥9,480税込

- 獲得ポイント :

- 29ポイント

当日発送可 (14:00までのご注文が対象)

- ※

ご注文内容・出荷状況によっては当日発送できない場合もございます。

詳しくはこちらよりご確認ください。

利用可

- ※

ポストにお届け / 一点のみ購入でご利用可能です。

ゆうパケットでのお届けの場合はサンプル・ノベルティが対象外となります。

ゆうパケットには破損・紛失の保証はございません。

詳しくはこちらよりご確認ください。

商品の詳細

商品説明

【商品説明】委託品となります。

放送局にて使用していた品になります。

動作環境がないため通電確認のみになります。

多少の傷やスレなどあります。

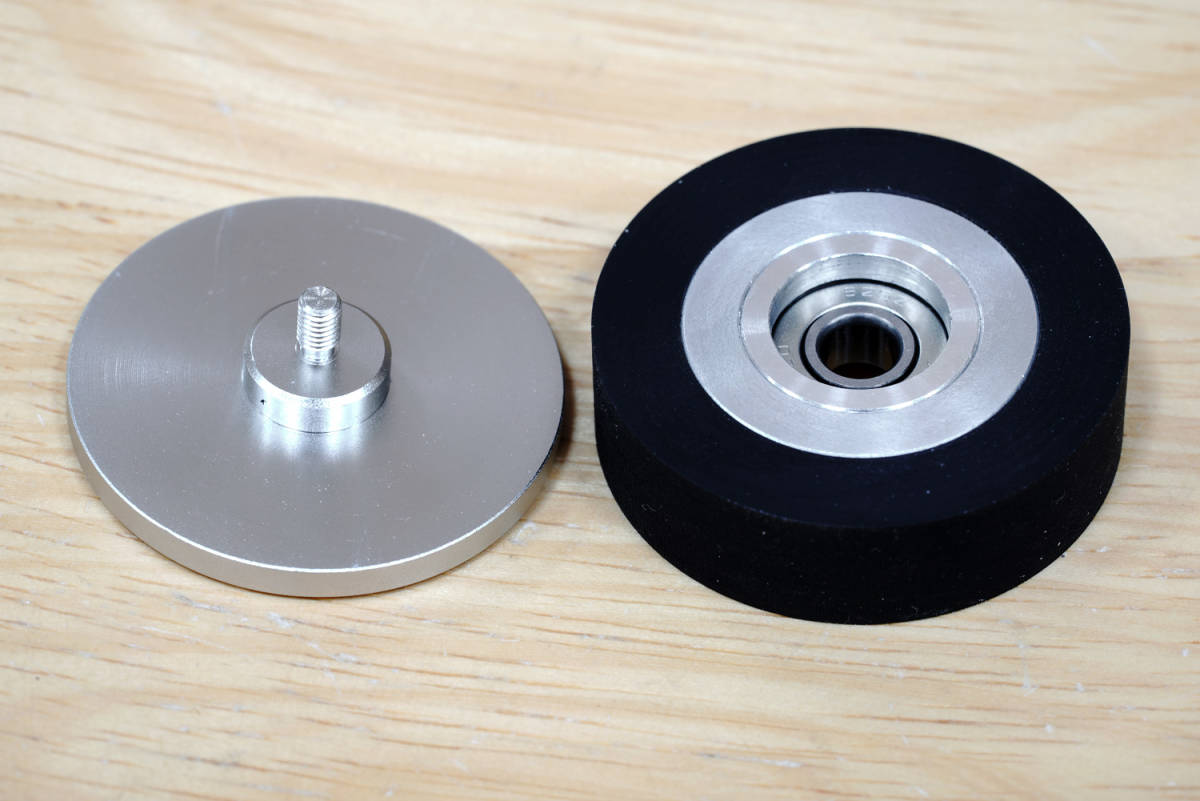

状態等は画像も合わせてご確認お願いいたします。

※上記状態のためご理解の上ご入札お願いいたします。

【付属品】

画像にあるものが全てとなります。

またタイトルに記載されている型番と相違したましても現物を優先させていただきます。

画像にて必ずご確認お願いいたします。

※一度、人手に渡っているお品物ですので

記載されていないダメージなどある場合が御座います。

自己紹介をご覧いただき、ご理解のうえ入札してください。

【注意事項】

商品によっては配送状況によ動作状況が変わるものがあります。

予めご了承くださいませ。

その際の返品およびクレームは一切受付いたしません。悪しからずご了承ください。

また返品などは対応しているかの項目から確認願います。

落札後、3日以内に連絡がない場合、入札札を取り消させて頂きます。落札に関して新規登録が簡単になったことで、迷惑な入札が増えています。新規の入札は削除いたします。本当に買う気がある方は入札時に質問欄にてご連絡ください。

新規の方が、即決などで落札した場合は、24時間以内にご連絡がない場合、即落札を取り消させていただきます。

発送は入金確認後、3日以内に発送させて頂きます。すぐに発送してくださいなど、落札後に対応できない場合がありますので、入札前に質問してください。

商品の説明

最新のクチコミ

お土産で頂いてから美味しくて何度もリピートしています!しいたけの味は旨味成分で出ているのだと思います。70代80代の両親も気に入り、まとめて購入しました。

- aaf*****さん

- 22歳

- アトピー

- クチコミ投稿 2件

購入品

美味しいコーヒーです。到着も早いので助かります。

- acd*****さん

- 27歳

- アトピー

- クチコミ投稿 2件

購入品

家電、AV、カメラのデイリーランキング

-

-

1

**品 Sony AF 50mm/f 1.4 レンズ*

¥17,020

-

![【新品(開封のみ)】 Panasonic コンパクトステレオシステム SC-ALL5CD-K ブラック [管理:1100053856]](https://auctions.c.yimg.jp/images.auctions.yahoo.co.jp/image/dr000/auc0501/users/49cec73d863172aefcb1e05297944ca3c682dc6c/i-img500x500-1705501522ekl1rr5753.jpg)