- 当日発送

- 送料無料

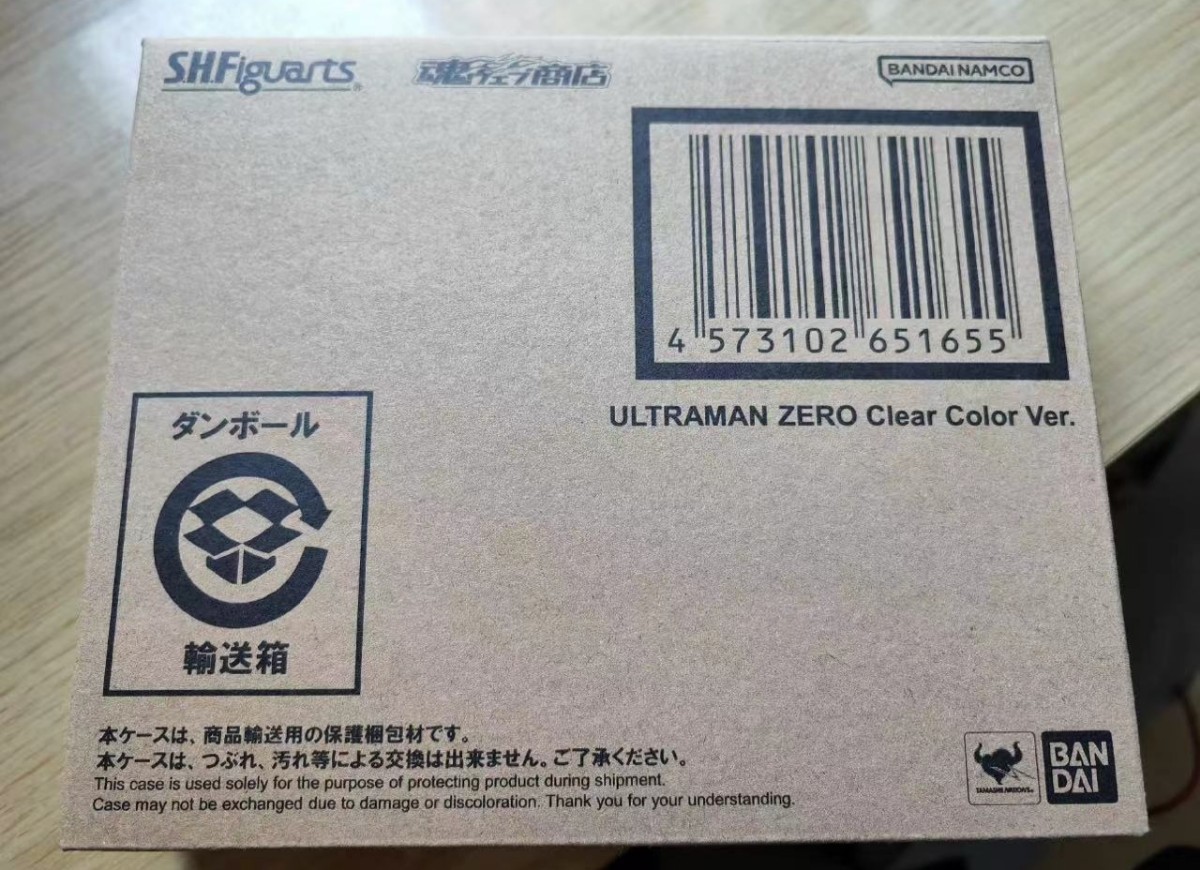

直営の通販サイトです S.H.フィギュアーツ S.H.Figuarts ウルトラマンゼロ Clear Color Ver. クリア 海外限定

- 販売価格 :

-

¥10,350税込

- 獲得ポイント :

- 21ポイント

当日発送可 (14:00までのご注文が対象)

- ※

ご注文内容・出荷状況によっては当日発送できない場合もございます。

詳しくはこちらよりご確認ください。

利用可

- ※

ポストにお届け / 一点のみ購入でご利用可能です。

ゆうパケットでのお届けの場合はサンプル・ノベルティが対象外となります。

ゆうパケットには破損・紛失の保証はございません。

詳しくはこちらよりご確認ください。

商品の詳細

商品説明

アジアバンダイ限定商品になります。お客様の大切な商品。丁寧に梱包してお届けします。

よろしくお願いいたします。

商品の説明

最新のクチコミ

お値段が安かったので期待していなかったのですが、大きくてしっかりしていてロゴもカッコ良く購入して良かったと思います。本人も気に入ってます。すぐに汚れてしまうので黒っぽいカラーも助かります。オススメです。

- fde*****さん

- 20歳

- アトピー

- クチコミ投稿 3件

購入品

お手頃価格で美味しかったです。

また購入したいです。

- eee*****さん

- 45歳

- アトピー

- クチコミ投稿 1件

購入品

長財布、スマホ、家の鍵、自転車の鍵を入れるのにピッタリでした。このサイズのバッグで内側にもポケットもあってすごく便利。既に持っていた太めのショルダーベルトに付け替えると更にイイ感じになりました。買って大正解!!

- bdf*****さん

- 24歳

- アトピー

- クチコミ投稿 2件

購入品

すっごく着やすいです。日本製に拘って購入してみたのですが、届くまで不安な他国のと違って色違いでも購入していて正解でした。又他のデザインのも是非購入したいと思ってます

- cde*****さん

- 46歳

- アトピー

- クチコミ投稿 2件

購入品